A changing landscape

From the last ice age onwards, Britain has been an ever-changing landscape. Forests came and went, vast grasslands contracted in size or opened up, huge wetlands covered river valleys and estuaries. During this time a huge variety of different animals suited to a cooler climate disappeared while others appeared before Britain’s land-bridge with mainland Europe was covered by rising seas around 8,500 years ago. Many animals that remained suffered from hunting and human-related changes as their habitats were destroyed. Today, Wildlife Trusts across the UK are helping to bring back some of those animals, like beavers and ospreys.

Here are 14 of the UK’s extinct animals and the stories behind their loss. Some became extinct thousands of years ago while others disappeared much more recently.

Auroch By Unknown - The American Cyclopædia, v. 2, 1879, p. 120., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39229005

Aurochs

After the last ice age aurochs, an ancient wild cow with huge curved horns, lived in low densities across Britain. They were the ancestors of modern cattle. As horses and reindeer disappeared from the landscape and moved into cooler environments, aurochs mixed with red deer, saiga antelopes, roe deer, wild boar and elk. They grazed on low-lying, open flat grassland, floodplains, birch woodland and even saltmarsh. Although larger than modern-day cows, they were hunted and eaten by bears, wolves and people. They died out just over 3, 500 years ago as hunting, farming and an increasing human population pushed them out.

Apple bumblebee

The apple bumblebee loved sand dunes in the UK and was found at a handful of sites in Kent during 1857 and 1864; it has been extinct ever since. Where they are found in greater abundance in mainland Europe they use a wider range of habitats such as marshes and woodland edge. And despite their rarity here, abroad they feed on a range of flowers with queen bees particularly partial to red clover. Found in Kent over 150 years ago, it is quite likely the apple bumblebee was an occasional visitor to Britain, on the edge of its range.

Lynx

Eurasian lynx are a woodland species and are specialised in hunting small ungulates such as roe deer. Eurasian lynx has been absent from Britain for hundreds of years, and by the middle of the 20th century it had also been lost from much of Europe. The latest radiocarbon dating on lynx bones reveals they were still in northern Britain approximately 1,500 years ago. The dating from bones gives us ‘hard evidence’ of lynx being present, but the records in written literature such as books and poems mention lynx in the British landscape up until the 17th century. As the lynx re-emerge across parts of Europe and suitable habitat is identified in Britain, a lynx reintroduction could be a possibility. Could we soon live alongside this species once again?

Lynx ©David Castor (Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lynx_lynx-2.JPG)

Wolf

Persecuted to extinction by 1760 in Britain, the wolf was a successful predator after the last ice age. It feasted on a myriad of deer, aurochs, bison, saiga antelope and other mammals that thrived across the open grassland and woodlands thousands of years ago. In caves, remains of wolves suggest they were domesticated as early pets for protection and help during hunts. Despite our relationship with their ancestors, dogs, wolves were not tolerated and gradually killed off. Unlike the lynx, the wolf survived in Britain for much longer, less reliant on the disappearing forests for cover and thrived on red deer which had adapted to the open Scottish moors.

Elk

The elk (or moose) was a common sight across Britain before disappearing 8,000 years ago, Sharing forests and woodland clearings with roe deer, aurochs, wolves and wild cats. Humans hunted them for meat and skins; their huge antlers were used as tools such as pick axes. Despite their success after the last glaciation, changes in the climate, vegetation, hunting and fragmentation of their environment, saw them disappear from the British landscape. The similarly named Irish elk was in fact a type of extinct huge deer that lived up until the end of the last ice age, 11, 700 years ago.

Brown bear

The brown bear was a common top predator alongside the wolf and lynx following the last ice age, after lions and hyenas had disappeared. It is calculated there were over 13,000 bears in Britain 7,000 years ago. Brown bears would have been feeding on a range of large mammals including deer and bison, while eating berries, roots and plants during leaner times. They are thought to have gone extinct in the UK just over 1, 000 years ago; gradual and persistent persecution, alongside the loss of its forest habitat, saw the brown bear disappear from our landscape forever.

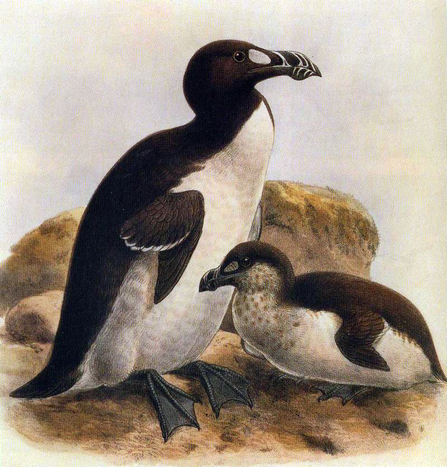

Great auk

The great auk was almost twice the size of the similar-looking razorbill, which can still be found at coastal breeding sites around the UK. Flightless, the great auk was like the penguin of the Northern Hemisphere, though from a completely different family. It lived across the North Atlantic and, like guillemots, preferred to live in large colonies at just a few sites including St Kilda, in the Outer Hebrides. Eggs were harvested and great auks killed for their meat and skins - the flightless birds were easy to round up on beaches and rocky ledges on islands. The UK's last great auk was killed in 1840, and just four years later the species became globally extinct.

Great auks by John Gerrard Keulemans, c1900 (Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Great_auk_with_juvenile.jpg)

Bison

Bison were once found in the British landscape, although archaeological evidence suggests they were more common on cold tundras of Britain before the last ice age, going back tens of thousands of years to a million years ago. They would have been mixing with woolly rhinos and woolly mammoths, and been eaten by hyenas, sabre-toothed cats and humans. Living in large herds, bison enjoyed the vast open landscapes known as mammoth steppe that replaced swathes of forests. As the climate warmed the bison disappeared; reindeer, wild horses, aurochs and deer dominated the grassy landscapes which slowly became woodland.

Grey whale

The grey whale is an animal we're used to seeing on television shows recorded off the Pacific coast of Mexico, where inquisitive animals actively come to boats. They make remarkable migrations north along the west coast of North America to feed in the rich northern waters over summer. Grey whales used to make a similar journey in the Atlantic; it is speculated that these animals migrated from breeding grounds between the Bay of Biscay and the Moroccan coast, north to the Baltic Sea to feed. There are records from Cornwall dating back to 1,329 years ago, and Devon claims one of the latest records of this species in the Atlantic, in the year 1610. The Atlantic population quickly plummeted, most likely as a result of hunting, until it was lost completely around 400 years ago.

Large copper butterfly

This striking, bright orange butterfly looks like it is wearing a high-vis jacket. While the small copper is still a familiar sight, the large copper went extinct in the late 1800s. The butterflies living in Britain were a unique variety, different to those found across the North Sea and Channel on mainland Europe. Like many butterflies that have disappeared from the British countryside, the large copper required a very specific environment; it loved wet, boggy fenland and water dock for its caterpillars to feed on. As meadows, marshes and reedbeds were drained from 1634 , their food plants disappeared, and the butterfly was unable to survive.

Large copper butterfly ©Sharp Photography [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Dalmatian pelican

The Dalmatian pelican reflects a time when huge areas of the UK would have been covered in reedbeds, marshes and large shallow stretches of water, like the Danube Delta in Romania, where this species lives today. It was common 12,000 years ago and bones have been found in peat bogs in Norfolk, East Yorkshire and Somerset from the Bronze and Iron ages. Eventually, 2,000 years ago, the drainage of these wetlands, alongside hunting and disturbance, led to the extinction of the pelican. Dalmatian pelicans thrive in northern Europe’s cooler climate. White storks and common cranes followed the same fate in later centuries, although cranes have recently returned to the UK.

European pond terrapin

Thousands of years ago Britain was home to over a dozen reptiles and amphibians, many now extinct here. One, the prehistoric-looking European pond terrapin, would have been common in wet and damp habitats, mixing with moor frogs, beavers and grass snakes; it went extinct in the UK around 8,000 years ago. This species is a familiar sight today in watery habitats across mainland Europe, and is different to the red-eared slider that was released into ponds in the 1990s during the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle craze. Their remains in archaeological digs reveal a time when the UK was much hotter. Relying on the sun to incubate their eggs, average July temperatures of less than 18°C saw the terrapin lose its grip in the British countryside.

Beetles

A range of beetles once lived here that now live in colder places such as Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau. They were able to survive in very cold winters and warming summers. Some were dung beetles, feeding on open grassy plains on the dung left behind from wild horses, elk and aurochs, woolly rhinos and elephants. Warming temperatures meant the beetles were unable to survive, retreating to cooler climates, following their shifting habitats and hosts as reindeer and horses headed north. More recently, the large, shiny horned dung beetle went extinct in Britain in 1974, disappearing as its favoured grasslands become intensively farmed.

White stork

Just over 600 years ago the last pair of white storks nested in Britain; they had suffered from hunting and the loss of watery habitats. They enjoy large open marshland, rivers, dykes and wet farmland, much of which was already disappearing in Britain, even in the 1400s. In areas where more traditional methods of farming are used, an abundance of grasshoppers, worms, frogs, snakes and fish thrive, providing an ideal food supply for storks. They are large birds, bigger than a heron, parading across fields with their white bodies, blood-red beaks and black wings. To help them re-establish, white storks are being reintroduced at the Knepp Estate in West Sussex. They may also benefit from the reintroduction of beavers to the UK, which create the kind of watery habitat that storks need to thrive.

Wildlife on the edge

It's too late for many of the species on this page, but much of our wildlife today is in danger. Hedgehog numbers have plummeted, natterjack toads are found in just a few remaining strongholds and farmland birds are declining at an alarming rate - if nothing changes, the purring of the turtle dove could disappear from our countryside completely. We need to act now to halt the declines and let wildlife recover.

Jon Hawkins, Surrey Hills Photography

Help prevent more wildlife from disappearing

By becoming a member of your Wildlife Trust you can help care for wildlife and wild places, prevent more species from disappearing from our landscape, and even bring back some of those we've lost.